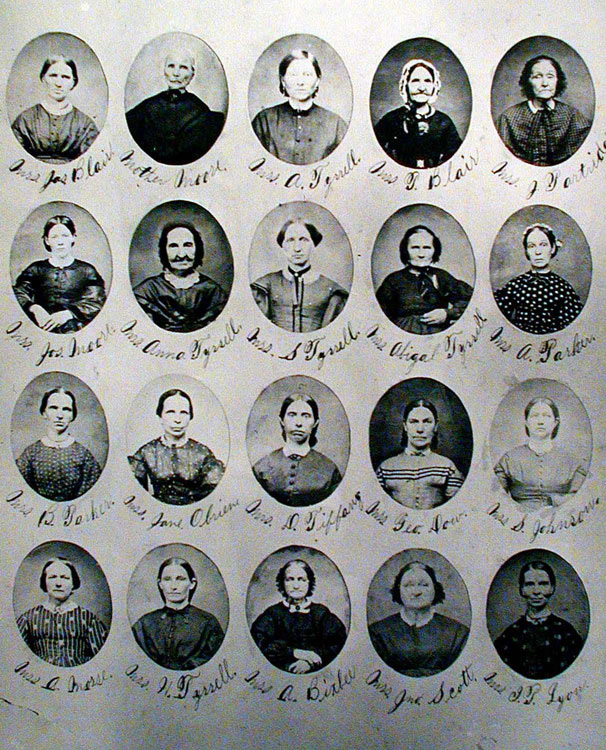

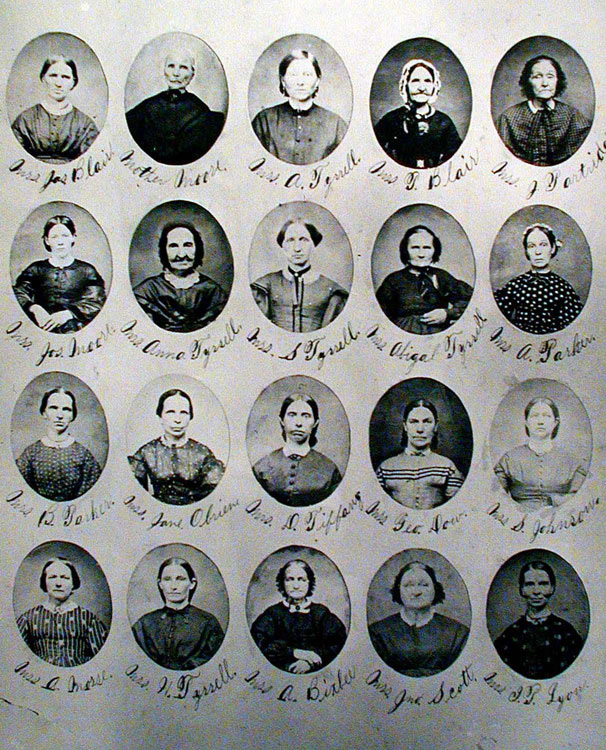

Submit (Mitty) Wait Graves Moore

(Top Row, Second Picture)

Stockton Herald News October 5, 1927

"THE MITTY WAIT GRAVES, MOORE and DIVELY REUNION

Submit (Mitty) Wait Graves Moore

(Top Row, Second Picture)

Stockton Herald News October 5, 1927

"THE MITTY WAIT GRAVES, MOORE and DIVELY REUNION

On Saturday, Sept. 3, 1927, at Lena Campground, Lena, Ill., 79 descendants of Consider Graves and Submit Wait met to pay honor to the memory of Submit. Those residents of both Stephenson and Jo Daviess Counties were those loyal to the traditions of good will and fellowship which have so largely marked the social intercourse of the family for so many years. By noon most of the 79 descendants present had scurried up in lunch-laden cars, and after registration and greetings were over, all present were seated at one long groaning table, beneath oak trees that have watched over their devout forbears since the thirties.

Owing to the sultry stillness, the afternoon program was held in the open shade, and proved to be most delightful. The subject of the day was the life and personality of Mitty More, born Submit, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Asa Wait. These parents were the most remote forbears of the Graves Moore family in its middle western history. The oldest granddaughter of the Moore family, Mitty Moore Sharp of Stockton, Ill., delivered the address, and carefully worked out many distinctive traits and experiences of this brave little pioneer woman.

Born in Hampshire county, Mass., March 16, 1782, of pioneer, Puritan stock, Submit Wait, with her father, removed to New York, settling in Norwich, Chenango county in 1787. There she married the young farmer, Consider Graves, in 1803. In 1810, with two small children, Hubbard and Elvira, they began the initial stages of their hegeira (sic) to the middle west driving by wagon to Pittsburgh, and descending by raft the Ohio River to Portsmith, Ohio. Attracted by the great fertility of the Scioto Valley, they purchased land.

As the wife of a farmer and frontiersman she bore six sons and daughters. Then the husband of fifteen years was drowned in the Ohio River in 1818, and the little family struggled ahead in an adverse wind until a friendly sail appeared in the person of Phillip Moore, who was married to Submit Graves in 1821. Three years later she buried her second husband, richer in the possession of another little son, Joseph Moore, Muleted (sic) of her timber lands, and struggling as best she might to raise a God fearing family in a roistering frontier riverport, she conceived the idea of opportunity for her boys, fine cheap land lands in a country with a future. Her neighbors and kin, the Robeys and Waits had gone on some years before. Her husband's nephew living in Ashtabula county, Ohio (Dexter Graves) having anticipated the wonderful opportunities afforded by the Illinois parries and the lake region, had proceeded to Chicago to resume his calling of hotelsman.

The call of the west became supreme, and in 1837 she gathered her family (now including two small grandchildren, William and Margaret Dively), and all arrived at Galena, Ill., in May 1837, via the Ohio and the Mississippi rivers. Several months were spent in prospecting in both Stephenson and Jo Daviess counties, but in order to be near the county seat and midwest metropolis, Galena, she finally settled near Wards Grove, Ill. Government lands were taken up, and each son was provided with a goodly farm. They could only do this serially as the mother had $100, which she loaned to each son in turn as he could use it. Her own sons had inherited $100 each. Her youngest son, Joseph, having inherited a larger sum from his father, Phillip Moore, could make larger investments in land and so laid the foundation of the estate which he owned in his mature years.

The earliest residence was built on Yellow Creek, three miles east of Stockton, and on-half mile north of the present Grant highway. It was a simple one-roomed structure of logs, with a loft to which the agile youths ascended to sleep; and from which they descended with pockets filled with nuts to be cracked at the stone hearth while their breakfasts were cooking. In winter their faces might be warmed at the fireplace, but their backs ran in shivers, and their coffee cups froze fast in the saucer. When the son Charles was married to Lury Anna Searles in 1842, another log cabin was built immediately beside the first, and a common front porch made family visiting easy in all weathers. But such luxuries were countered by things not so fine. In New York the young girl Submit had cared for her motherless family of brothers and sisters amid many deprivations. There was no such thing as a washboard, so laundering had to be done by rubbing clothes between the hands. Fatiguing as this was, she had to follow this up for many years in Ohio and Illinois, with washing in kettles at the creek. When the washboard was invented and came into her possession, the relief it afforded her at work, she declared it to be almost unutterable.

If the pioneer woman of yesteryear, and of all the years before that might be given an emblematic insignium, it would be most seemly that it should be a strand of spun thread. That was the fulcrum on which every day of her whole existence levitated. From those earliest years that little hands would guide the wheel and distaff, to the days when almost sightless eyes could scarcely see the work, and only practised instinct fumbled on, the pioneer woman's time was spent groping along this little thread. In the full strong happy days it ran rapidly like a shuttle of gold through fingers that wound and shot the shuttle fast. The loom, the dye-pot, the cutting-out of garments waited the maturer years, as the thread turned merely silver. When it ran slow and leaden through the hand, the grandmother could but sit to knit and mend, and recreate from worn and faded habiliments, the frugal rug or carpet, quilt or comforter. Then came the day when the thread ran black and stopped forever; and the one who had dealt with it lay still, clad in a mere somber bit of all that life's work had created. Spun and measured and cut, she passed out into a great silence and stillness; her little thread thrown out, a web too touch and tangle countless other webs, --a nimbus, a halo, her crown. Thus she lived and thus she trained her daughters in the lore of flax and wool and cotton. What family did not have its reel and spinning wheels! And the Graves family have inherited theirs!

The early days had their graces. Water and wood were for the taking. Wild fruits abounded. Ice could be cut away in winter and abundant fish taken from Yellow Creek. Game was plentiful, and wild flowers romped in glowing hordes across the parries. The hawthorne and wild crabapples made glorious the banks of Yellow Creek in spring. The will o' wisps crept along the marsh in summer, and Aurora Borealis played her myriad lights in winter, with as much (illegible) color as a modern stage electrician. Amidst such natural charm, life could not become wholly sordid, and there was a recompense for toil.

Locomotion was not a happy thing in Mitty Moore's lifetime. Roads were poor, and cozy vehicles unobtainable; a spring wagon with a board seat was luxury untold. The frail body could not take many trips in later years, but when Illinois Central railroad had been put through from Freeport to Dubuque, a day's outing was arranged to take 'grandmother' to see for the first time in her life, a railroad and its trains. The desire was to see the passenger train, but fate forbade. However, the journey yielded the spectacle of a freight train; she never saw a passenger train.

Passing from the days when Indians looked in at her windows by night and by day; when wolves howled dismally and rattlesnakes resented each unwary step,--the time came when such alarms could be forgotten in the peaceful homestead of her youngest son, Joseph Moore. She lived to see her eldest son, Hubbard Graves, sent as a representative to the Illinois legislature in 1843-1844; later her youngest son was also sent.

In character devout, her Ohio home was a regular preaching place on Brush Creek Circuit, Scioto County. In 1832, Henry Bascomb, a noted orator of the day preached there. This custom was resumed in Illinois.

Her moral latitudes read curiously as she could not tolerate music in churches, but did believe in dancing as a social grace, duly teaching her family the art; and further she claimed the pioneer woman's privilege to smoke her pipe of clay, but she would not 'snuff.' All this may have shocked the sensibilities of her grandchildren, but Time smooths out quite painlessly many heresies of the past.

Her last years were spent daily with her Bible, Book of Psalms and Hymn Book. Her hope was to be as helpful in her home as possible, and all her life she dearly loved to have her many grandchildren close about her. Seated in her own rocker in her corner by the fire, her grandchildren watched her white-capped head and her black-shawled shoulders bend above the Word of God. Second sight enabled to read without glasses, and so she lived until April 27, 1874, when she passed peacefully away and was buried in the farm cemetery of her son, Homer Graves. A stone was erected relating simply her pioneer history. The body and stone were removed about 1900 to the Protestant cemetery at Stockton, Ill., and there rests calmly the remains of her who led her little flock from east to west, from poverty to affluence.

Her sons were Hubbard, Homer, Charles and William Graves, and Joseph Moore. Her daughters, Elvira Dively and Emily Rogers. All lived in this region, and their posterity largely remains in these parts.

Sept. 26, 1927 Mary C. Blair, Sec."

Picture and article contributed by Lyman Carpenter

Return to Photo Index